The poem below has been sitting on my computer for a year, and I decided it was finally time to let it go. I wasn’t tweaking it and I didn’t want to risk messing up the meter I’d established if I tried, so I figured it could at least sit on this blog rather than in my writing folder. A year is a pretty long time for me to let a piece of writing marinate. I believe part of the issue is my confidence that the poem is solidly mediocre. However, I set myself a challenge with this poem, and I think I learned a lot from it. Not everything has to be perfect, and I would never argue that I am or that anything I put on this blog is.

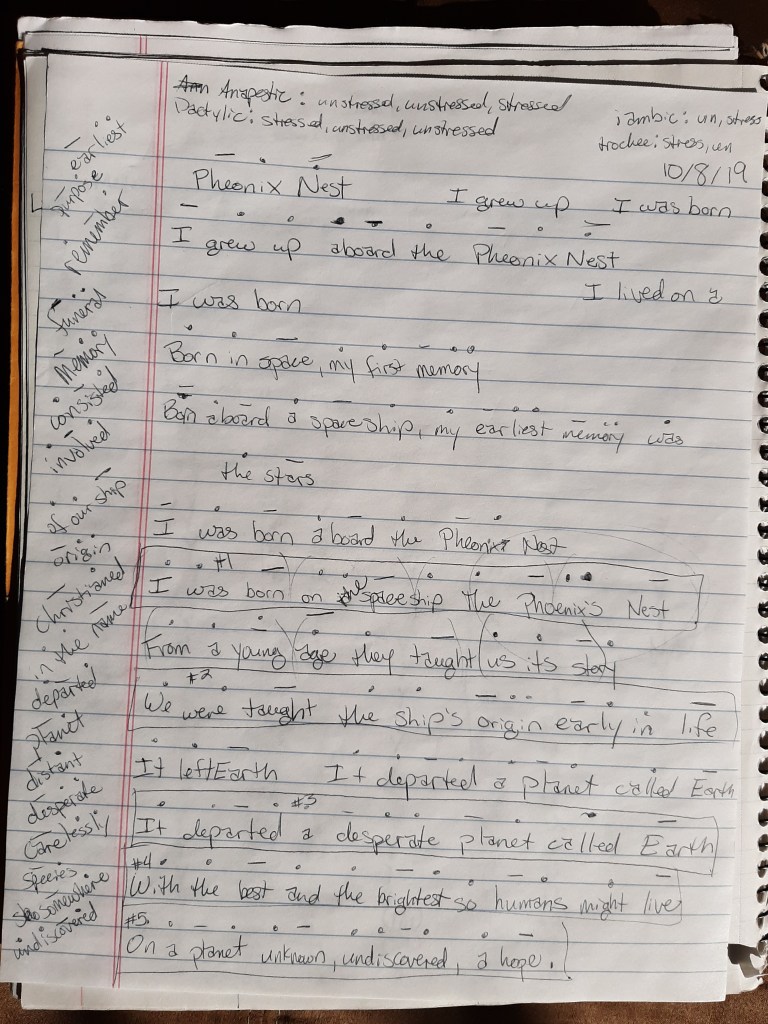

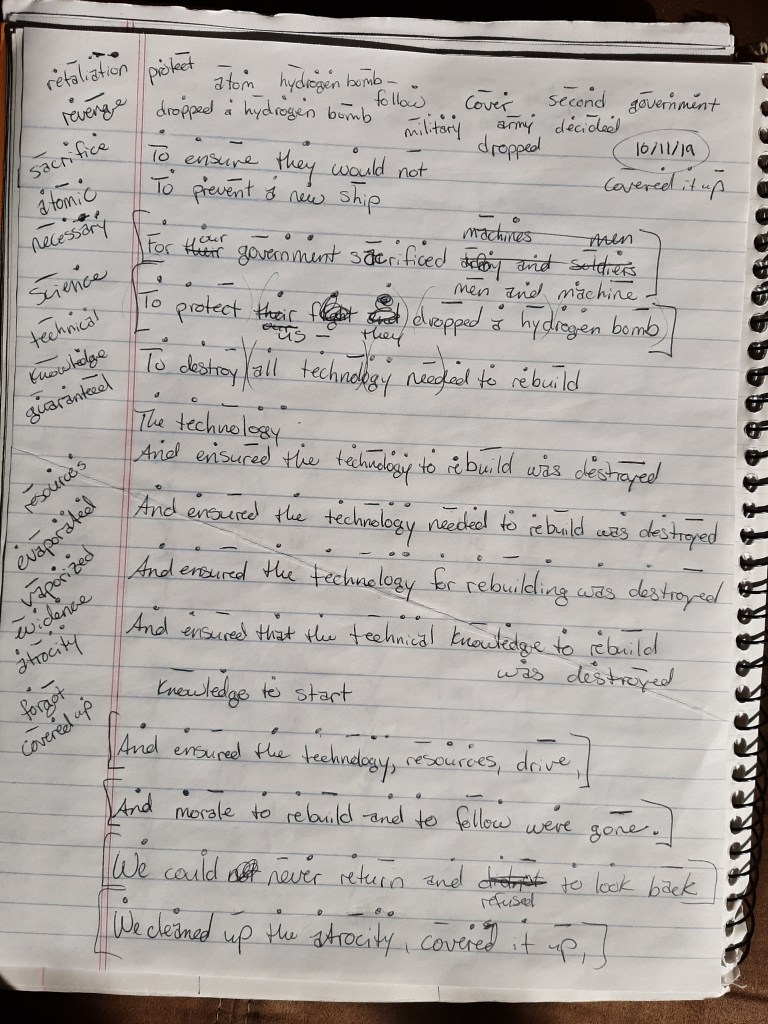

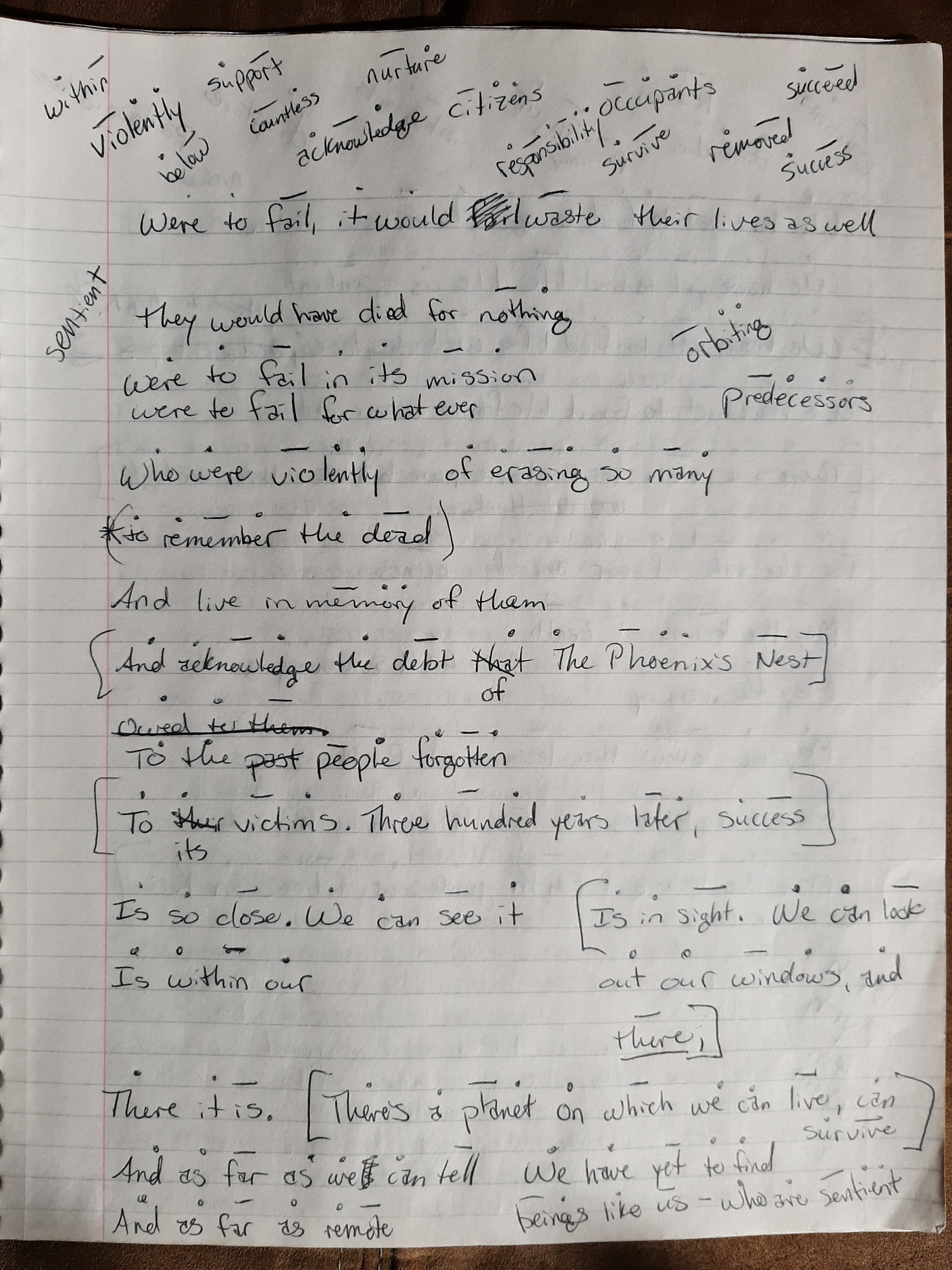

I chose to experiment with epic poetry because I wanted to write something expansive that told a story. The writing process for The Phoenix’s Nest took a month. I have 46 pages of scribbles, words with stress markers, discarded lines, and finished lines dated from October 8 to November 2. It was one of the most concentrated creative efforts I’ve attempted. The poem doesn’t necessarily fit into the typical definition of an epic poem. Among other things, an epic poem is book-length and involves fantastical or mythological events that happened in the distant past. Though 123 lines is long for a poem, but they are too short for a book, and the poem’s setting is the distant future. Of course, there’s nothing to say that an epic can’t be written in this manner, but a purist might take offense.

I chose to use anapestic tetrameter as my meter. This means four groups of three syllables per line (or 12 syllables total), and the syllables are unstressed, unstressed, stressed. I chose the anapestic style because I’d read somewhere that it (and its opposite dactylic, which is stressed, unstressed, unstressed) mimics spoken English fairly well. I chose tetrameter because that was where the first line I wrote naturally ended. A lot of those 46 pages of rough draft were me trying to figure out how to say what I wanted to say while staying within these confines. I worked to make the language feel natural, but some of it sounds stilted or contrived. Out of 123 lines, eight fail to be anapestic, six have 15 syllables rather than 12, one has 11 syllables, and one has 14 syllables. I allowed these exceptions for a number of reasons: a phrase ending naturally, to draw attention to a particular point, or because the extra syllables blended in with others and were barely noticeable.

During this writing process I internalized that sticking to a strict meter does not guarantee a smooth rhythm, or flow, while speaking or reading. I feel that the story is interesting, but sometimes the flow is a bit off. If you’re confused about what I mean when I say flow or rhythm, I would encourage you to read A Visit From St. Nicholas by Clement Clarke Moore. This famous poem uses the same meter that I used, but naturally flows from one line to another. In contrast, my poem is more like stop-and-go traffic. Part of this may be because I chose not to rhyme. Rhyming may have helped with the flow, but would also have imposed additional restrictions on what I could say and how I could say it (try rhyming massacre satisfactorily). Some people might ask why I went to all this trouble when I could have easily written The Phoenix’s Nest as a prose piece where rhythm and flow wouldn’t matter. My answer would be that I set myself a challenge and I intended to follow through with it. I’m happy I did, because it taught me there can be more to poetry than meter and story, and gave me a much greater appreciation for those poets who successfully wrote long, memorable epic poems that flow off the tongue.

I have one final note before getting to the poem. Usually I try to accompany my writing with a photo that I’ve taken myself. Given the science fiction and futuristic aspect of The Phoenix’s Nest, I didn’t have any photos that fit this requirement. Instead, I tried my hand at computer illustration using the free program paint.net (the website looks sketchy, but I’ve used this program for nearly a decade with no problems). I’m sure professional illustrators would cry to see what I put together, but I more or less accomplished what I intended with minimal knowledge and less skill: a spaceship approaching a planet.

The Phoenix’s Nest

I was born on the spaceship The Phoenix’s Nest. I am of the sixteenth generation aboard. I’ve committed myself to the ship and its crew – Their continued existence, improvement, and life – But The Phoenix’s ultimate mission is this: To discover a planet to live on again. We are taught the ship’s origin early in life. It departed a desperate planet called Earth, Which was withered and sick and practically dead, Because Earth was abused and malnourished too long. So a ship was conceived to survive in deep space. In the midst of a war it was built and supplied. It was finished, a lottery held, and was manned With the best and the brightest so humans might live On a planet unknown, undiscovered, a hope. Earth we fled and the Milky Way’s spirals explored, Sagittarius saw, and then Virgo was settled upon.

Near the Milky Way’s center, two centuries out, An historian found the records of departure from Earth. Some were documents, others were voice logs, and one, The most chilling of all, where breath stopped and blood froze, Was security footage of a massacre. We were chosen by lottery, but on the wrong side of war. On the night before launch when supplies were aboard And the crew and civilians asleep in their beds, We attacked with diversions and bombs, EMPs, And superior numbers and ruthless intent. They were caught by surprise and were murdered in bed With their families. All were replaced to a child. As The Phoenix’s Nest, the personified hope That humanity rise from the ashes of war, Rose above the combatants to flee into space, It was stained with the blood of three thousand and ten. We ejected the bodies in orbit, then left Behind Earth and our war and became refugees. For the government sacrificed men and machines To protect us and dropped a hydrogen bomb To ensure the technology, resources, drive, And morale to rebuild and to follow were gone. We could never return and refused to go back. We cleaned up the atrocity, covered it up, And pretended as if we were always the ones They intended to pilot The Phoenix’s Nest.

When the truth of The Phoenix’s Nest was released, There was tension already and people were mad, Were upset. The opinion that top engineers And the scientists, officers, and doctors were More important than those with less technical jobs – Such as garbage collectors, the janitors, cooks – Or perceived as a waste of the resources scant – Unemployed and the artists were frequently used – Was a popular one, at the time reinforced By a shortage of valuable resources caused By The Phoenix’s Nest population increase. Where three thousand and ten had begun, and despite Regulations designed to control the crew’s growth, The last census had counted four thousand nine hundred and twelve. There were plans for expanding The Phoenix’s Nest, With construction already progressing on them, But expansion meant mining surrounding space For materials needed to build, as well as Fabrication of building components to use, And support of construction activities too. All of this in addition to normal, routine Operations. Sometimes too much power was used And emergency black outs occurred to maintain The essential ship functions. Then people would run To identified safe zones and there they would wait To be given the signal that power was back. On occasion this wasn’t enough and a zone Would be lost. This was tragic, but random, so that Individuals had a fair chance to survive. This was happening frequently recently and The result was four hundred and fifty deceased. All three zones that had failed had contained those less skilled, Undesired personnel and suspicions were high That the randomization was disabled to allow The specific removal of people disguised As an accident. Many had spoken against The prevailing belief of their diminished worth, But the captain had openly ridiculed them. She had publicly mocked them, referring to them As “the parasites”, claiming The Phoenix would be More efficient without them around. It was said That she smirked when she heard of the loss of the zones. The conditions deteriorated without Personnel to dispose of the trash, or prepare Food for thousands, or launder the uniforms, fix A malfunctioning sink, mop a floor, watch a child. Productivity slowed, but the captain seemed pleased. In a crisis, such petty complaints went ignored. It was Dr. Elise Graham-Varkova, a head Mathematician and programming expert, who found That The Phoenix’s code had been changed to allow For a zone to be chosen to fail at the time Of a black out. The doctor had examined the code Because most of her family died in the zones. The reaction that followed was angry and loud And a time of reorganization commenced. Those in charge were convicted and thrown into jail. A new governing body was founded, and rules, Regulations, and rights were defined and enforced.

In this traumatized climate the truth of The Phoenix’s Nest Was revealed, and the shock waves continued for months. Their whole lives they’d been told they were scions of Earth, The protectors of knowledge and culture and faith, The descendants of brave pioneers who were destined for more. But the fairy tale shattered – not heroes, but thieves; They weren’t martyrs, but murderers painted in blood. Though the truth was unwelcome, The Phoenix’s Nest Did continue, for history could not be undone. But instead of the righteous ambition before, They were driven by penance, humility, shame, And desire to atone, to remember the dead And acknowledge the debt of The Phoenix’s Nest To its victims. Three hundred years later, success Is in sight. We can look out our windows and there, There’s a planet on which we can live, can survive. There’s a niche for us here, we believe. Hopes are high. Academics preserve the idea of Earth, but It is history, cultural memory, now. They’ve preserved its dark legacy, violent and grim. May the lessons we’ve learned guide our actions on Kiri.